A Reflection for the Sunday following the 4th

of July All Saints’, Southern

Shores, N.C. July 6, 2014 Thomas

E. Wilson, Rector

On

“Lives, fortunes and sacred honor”

A video version of thei sermon is on You tube: http://youtu.be/Fqw6Zc-q0OQ

Today we have moved the lessons for the 4th

of July to take the place of the lessons for this Sunday. The Episcopal Church

has had an ambivalent history with the 4th of July, that day in 1776

in which people pledged “with a firm reliance on the protection of divine

Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our

sacred Honor,” for this dream of a nation in which all are created equal. Not

all the people who make up the Episcopal Church pledged their “lives, their

fortunes and their sacred honor” for the cause of Independence. In 1775, when

the Revolution began, there were about 300 congregations of The Church of

England in the thirteen colonies. The Church of England was the established

church in six of the thirteen colonies: Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina,

South Carolina, Georgia and New York.

Establishment meant that they were

supported by taxes of all citizens; indeed, one of the contributing causes of

the Revolution was the idea that that taxes were going to pay for the Bishop of

London’s palace in England. We still have a remnant of the idea of the state as

controlling religious thought in Article VI, section 8, of our state constitution

which denies the ability to hold elected office to “any person who shall deny

the being of Almighty God.”

| |

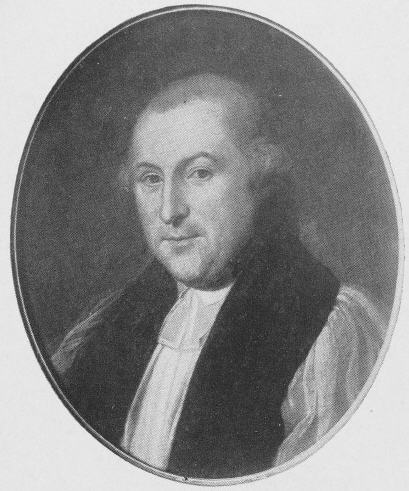

| Samuel Seabury |

The title “Episcopal” means having Bishops, and we started

off as a church with three Bishops.

The first, by order of consecration, the Bishop

of the American Episcopal Church, was Samuel Seabury who, as a loyal Priest in the

town of Jamaica, New York, a part of Queens, had written pamphlets opposing

disloyalty to the British Crown. When the war began, he was jailed by the

patriots for a while, and then when the British drove Washington’s Army out of

the New York City area, he was appointed Chaplain to a British regiment. After

the war he got out of town, moving to Connecticut, and finally swore loyalty to

the American side.

|

| William White |

The second Bishop was William White of Philadelphia, who was

the only Anglican Priest in Pennsylvania to support the Patriots’ side, and he served

as Chaplain to the Continental Congress.

The third was Samuel Provoost of New

York, who decided that he could not remain as Assistant at Trinity, Wall Street,

and continue to pray for the King, so he stepped down for the duration of the

war. While he did not join the Patriot army, he did join an armed group that

chased a retreating British troop in retaliation when the British burned down a

town in which he was staying.

The third was Samuel Provoost of New

York, who decided that he could not remain as Assistant at Trinity, Wall Street,

and continue to pray for the King, so he stepped down for the duration of the

war. While he did not join the Patriot army, he did join an armed group that

chased a retreating British troop in retaliation when the British burned down a

town in which he was staying.

During the war, some states confiscated Church of

England buildings, turned them into state property, and sold off church lands,

and it took a while for them to be returned to use as worship spaces after the

Revolutionary War. By the end of the war, 40% of the Anglican ministers left

for Canada. The battered and divided remnants of the Church of England in His

Majesty’s Colonies under the authority of the Bishop of London, the Anglican

church, started making a slow and painful transition to the Protestant Episcopal

Church in the United States with a move to celebrate the 4th of July

in the lead up to the first Book of Common Prayer. The three Bishops decided

against this move since many of the Priests had been on the loyalist side, and

this would only rub salt in the wounds. So the Episcopal Church begins by

binding former enemies together. We can assume that the Priests, and

parishioners, didn’t always like each other, but they decided to love each

other because they believed as the lesson from the Book of Hebrews for today

tells us, that “they confessed that they were strangers and foreigners on the

earth”; our true homeland is not of this earth. However much we love this land

in which we live, no matter how long this earthly life, we are only passing

through, and our allegiance, our deepest commitment, our highest passion is to

a higher law than the Constitution and a higher Judge than the Supreme Court.

We may, some should, none must, have a passion for

our earthly country. Passion comes from the Latin “patere” which means “to suffer” and means having a very strong

commitment to a person, place, or thing and being willing to undergo suffering

for the commitment to that person, place, or thing. That suffering of the heart

and soul and mind in devotion to God’s Kingdom was the basis of Jesus’ earthly

mission and ministry, and it culminates in his last days during what we call

Passion Week.

There are two levels of passion - one for God and

the other for those people, places, and things that are in our lives. I

remember a conversation over our family supper table almost 50 years ago. I was

home from college and my older brother, Paul, was home from Marine Boot Camp.

Paul was talking about being a real “Gyrene” and going to Vietnam and “kill

some Cong”. I opined that I could never kill another human being. My father,

who had been a Major in the Marine Corps during World War II fighting in the

South Pacific turned to me and, pointing his finger at me, said, “If you don’t

want to kill someone - aim high; you don’t owe your country someone else’s life,

but you do owe your country your life.” Then turning and

pointing to Paul he said, “You owe your country your life, but not your mind.”

My father passed on that kind of passion where you

accept the person, place, or thing as the gift that they are, but then look

deeper than just the outside persona and see the potential in who or what they are

created to be. The saying is true - the opposite of love is not hate, it is

indifference. We can love someone but hate the things they do, whereas

indifference means that they are not worth expending the energy to feel

anything toward them. Love is the way I

look at my family, my country, my friends, my church, and myself. I love my

family, my country, my friends, my church and myself, but I do not see them as

perfect with a “My country right or wrong, love it or leave it” kind of

mindless mentality. I love these all, faults and all, as works in progress, and

I love them enough to stay and help. Our task for our country is to have

passion and spend time, energy, and money to help it grow into the dream which

called it into being. It means being honest about its failings when we as a

nation fall so short of the divine vision for us.

Today we remember this nation and, as we give thanks

for it, we also commit ourselves to be in the image of God who, as the reading

of Deuteronomy reflects, “is not partial and takes no bribe” (which suggests

that we may need to do better work about tax breaks, lobbying, and funding of

elections), “who executes justice for the orphan and the widow” (which suggests

that we have work to do on caring for the poor), “and who loves the strangers,

providing them food and clothing” (which suggests that we may need to do more

work on how we deal with immigrants). “You shall also love the stranger, for

you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (we here on the Outer Banks know more

than a little about being from somewhere else).

When I was growing up in the Episcopal Church, after

we shook people down for money with the offering plates, we would all sing the

doxology and then the organ would crank up for the last verse of “America”. I

used to harrumph about it because it seemed a response to the McCarthy era, but

it seems appropriate for us to go to the past and proclaim our passion for our

country with the greater passion for our God. Our country has a past and is

always in transition to the future, and while we are on this passionate road

committing “our lives, fortunes and sacred honor” to our country, we also are

in transition to a different homeland. Let’s sing the last verse of Hymn 717 as

a sung closing prayer, to be followed by a spoken prayer:

Our fathers' God to Thee,

Author of liberty,

To Thee we sing.

Long may our land be bright,

With freedom's holy light,

Protect us by Thy might,

Great God our King.

The spoken prayer was given to me by

one of our members who used it to open a meeting of the Worship Focus

Committee. It is by the Reverend Canon Kristi Philip of the Diocese of Spokane,

and it is called “A Prayer for Transition”:

Ever-present God,

You call us on a journey to a place we do not know.

We are not where we started.

We have not reached our destination.

We are not sure where we are or who we are.

This is not a comfortable place.

Be among us, we pray.

Calm our fears, save us from discouragement,

And help us to stay on course.

Open our hearts to your guidance so that our journey to this

Unknown place continues as a journey of trust.

Amen

No comments:

Post a Comment